A white, triangular figure with two cartoonish black eyes crafted from heavy brushstrokes; meaty hands smoke a cigarette and paint a self-portrait. Buckets of paint sit in the foreground and a singular light bulb, a window and a clock with one arm adorn the fleshy pink wall. This is Philip Guston’s “The Studio,” displayed at his exhibition at Tate Modern.

Known for his carnivorous palettes of pinks and reds, thick black lines and cartoonish paintings of Ku Klux Klan members, Philip Guston was never an artist of staticity.

The Philip Guston exhibition at Tate Modern triumphs in showing Guston’s artistic dexterity, personal energy and political drive.

Consisting of 11 rooms, the show is a chronological retrospective of Guston’s life and exhibits different stylistic periods of his art. The show opened Oct. 5 and closes Feb. 25.

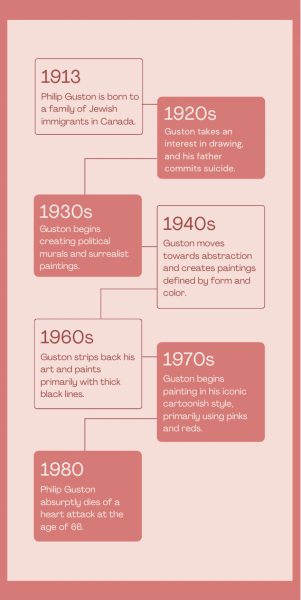

Philip Guston, born in 1913, was a Jewish American-Canadian painter and printmaker. Guston experienced many tragedies in his early life, such as the suicide of his father and the death of his brother. This darkness and moral anxiety was expressed later in his paintings through symbols such as clubs and limbs.

From a young age, Guston showed an interest in politics and created socially engaging protest art in reaction to the growth of hate groups, specifically with racist, anti-semitic or fascist beliefs.

The 1930s

The exhibition, in concordance with Guston’s career, begins with his mural paintings. Guston’s murals are unsettling and brutally unafraid – in the 1937 anti-war painting, “Bombardment,” an explosion of color and darkness at the center of the circular canvas throws swirls of fabric and bent bodies toward the viewer while planes fly overhead.

It is in these surrealist paintings that one first admires Guston’s technical ability: his precision of brush stroke, use of color and depiction of light. It almost appears like a soul has been put into these disturbing images as he masters surrealism.

The 1940s

Hence, Guston experiences a creative crisis in the 1940s as he becomes dissatisfied with figurative painting and starts moving towards abstraction. This is where the exhibition moves next, and where Guston first shows his incredible artistic dexterity. In these large paintings full of color and form, Guston is driven by the energy to create and an urge to reveal what he sees in the world through his art.

Not only does he transition to an entirely different style of painting, but he does so skillfully. Paintings such as “Fable” and “Beggar’s Joys” are composed of dense forms built of feathery brushstrokes, expressing an internal energy fighting to get out. Guston’s raw energetic frustration to grow and explore reaches out to each observer.

The 1960s

In the 1960s, Guston strips back his art and begins painting with black lines that spill over the canvas in varying thicknesses and forms.

Once again, this next room in the exhibition is a drastic change from the one preceding it. Guston has continued to be pushed into a new style of painting and prove his incredible artistic ability to its audience.

The brushstrokes on these pieces are raw and simultaneously constrained and liberated; the path of the brush is undetermined in nature, yet completely controlled by Guston himself.

The early 1970s

In the 1970s Guston entered the most productive period of his career. Primarily painting with fleshy pinks and reds, he creates strange dreamlike scenes of everyday objects. Here the viewer can see symbols from Guston’s own life come through his work: cigarettes, boots, clubs and body parts.

It is in this phase that Guston creates his most iconic symbol: the hoods. With white triangular characters with large black eyes as their only feature, the cartoons depict members of the Ku Klux Klan in a grotesquely comical manner.

Painting, driving a car or smoking a cigarette, the triangular hooded figures are pathetic and humanized. Guston has made them non-threatening, taking away their power and ridiculing them in a way that is disturbing and thought-provoking.

Through his paintings, Guston is fearless in his message that evil can lurk anywhere. In ordinary life, in the self; doom and darkness are parts of life. His darkly whimsical hooded figures will go on to become one of his most recognizable yet controversial symbols, sparking discussion even now, almost 50 years later.

The late 1970s

The final room of the exhibition is named “Night Studio,” and depicts some of the paintings Guston created towards the end of his life featuring self-portraits curled up in bed, a lone kettle steaming away and palettes of heavy red and black.

There is a visceral, raw sadness in this room. The viewer has witnessed Guston’s life: the exhibition is a personal view into his nightmares, his relationships, his growth, his restlessness and his energy. Watching it end is gut-wrenching.

Each room is a different decade and a different style. Each new style is growth and experimentation, all highlighting Guston’s incredible artistic skill and dexterity as he navigates through surrealism, figuration and abstraction throughout the decades. The chronology of the exhibition immerses the viewer in Guston’s life as he experiences personal hardships and politically turbulent times. He is undoubtedly present in every single room, in every single decade.

The exhibition overflows with love, protest and vehemence. The viewer gets a front row seat to witnessing the incredible artistic dexterity, personal restlessness and political voice of Philip Guston.